15 Years of LAFF – Reflections from a Current Volunteer

When I joined Latin American Foundation for the Future as a volunteer, I didn’t know that a key part of my role as Communications Coordinator would be celebrating LAFF’s 15th anniversary through social media and a fundraising campaign. This experience has proven to be a unique opportunity to get to know the organisation from its beginning until now. Sifting through beneficiary stories, volunteer testimonials, and statistics, I have been able to learn about and understand LAFF’s impact over the years while searching for content and memories for the 15th anniversary celebration – a perspective I might not have gained otherwise.

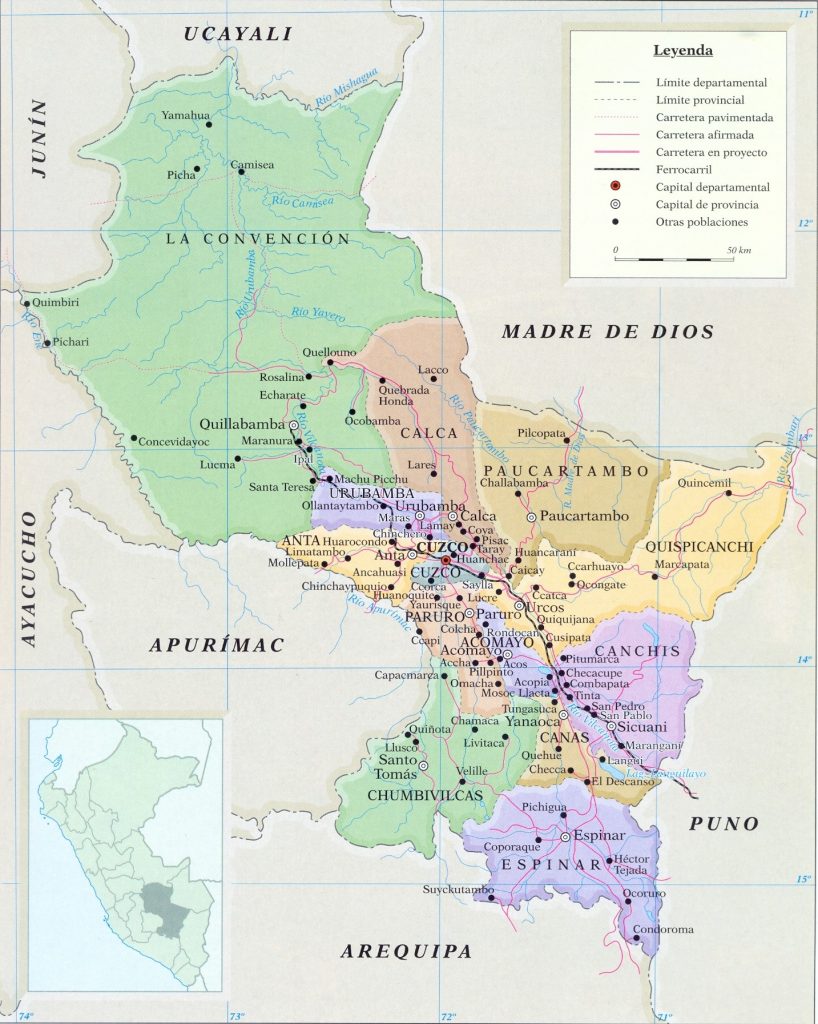

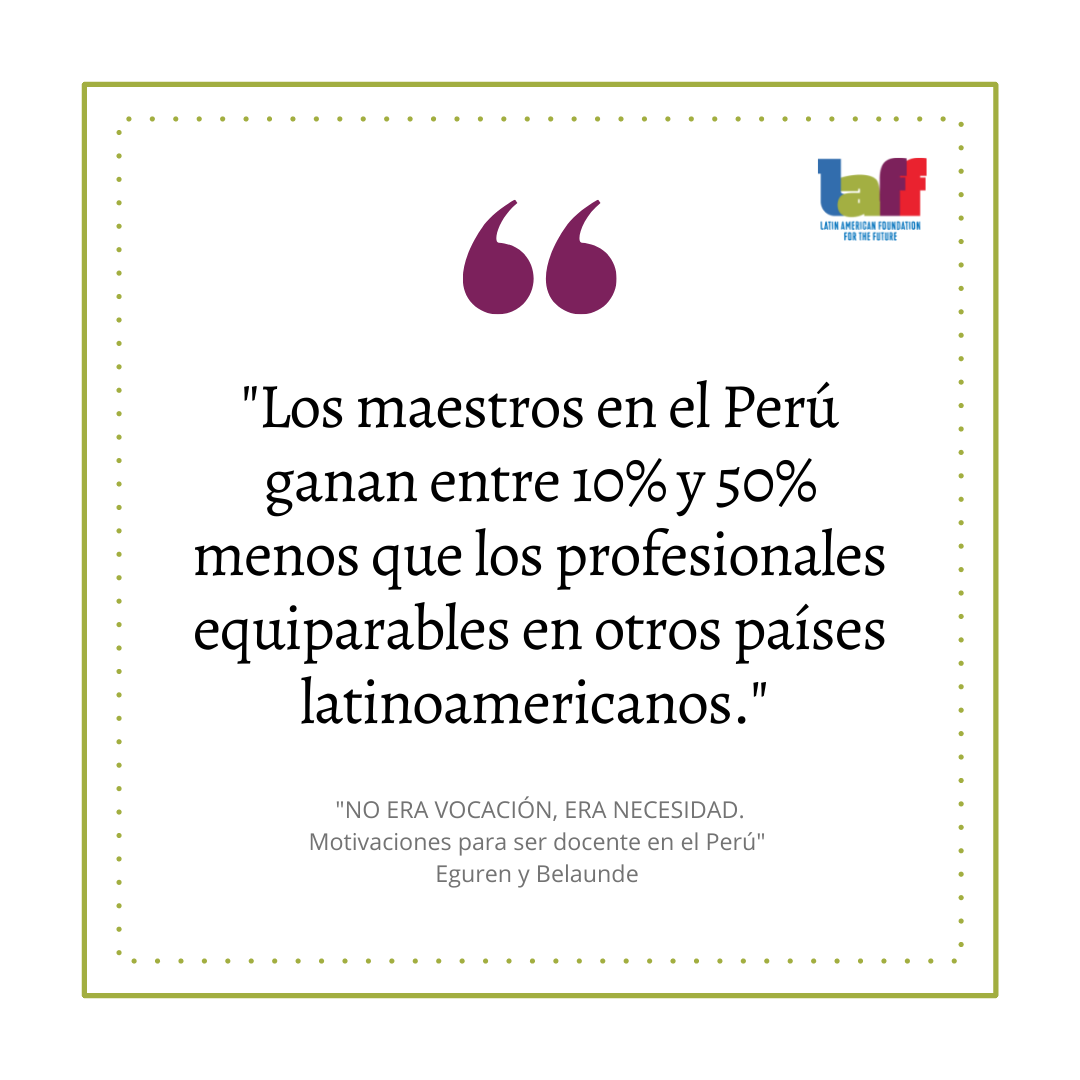

As I delved into the archive, I discovered just how much LAFF has grown. Its journey cannot only be measured in terms of impact and scale but equally in its commitment to its core values. Established in 2007 by its founder, Sarah Oakes, LAFF initially extended its support to one local partner organisation – Azul Wasi, a home for vulnerable boys. Sarah’s inspiration led to the creation of an NGO devoted to facilitating access to quality education, personal development, and better opportunities for children and young people in Cusco and the Sacred Valley. Over the course of the subsequent years, LAFF’s family expanded, partnering with three new local organisations – Mantay, Mosqoy, and the Sacred Valley Project.

It’s difficult to say how many volunteers have shared part of LAFF’s journey, but each has left their mark in a different way by giving their varying amounts of time and diverse skills. While some come and go, there are those who have stayed connected to LAFF. Only a few weeks ago we were visited by a former volunteer from 2016 who was delighted to catch up on our progress, and we also have trustees who were once volunteers and still continue to support LAFF in a different way. The genuine, continued commitment of those who’ve been part of LAFF’s programmes is an attestation to the authenticity of our values and goals, and it’s heartwarming to see how many are eager to stay engaged and connected. Many volunteers will remember their time at LAFF as a very special moment in their lives. I know I will look back on my time with the team at LAFF very fondly, as a time of friendship and personal growth. I have learned so much not only in the realms of professional experience but also regarding the people, culture, and history of Cusco.

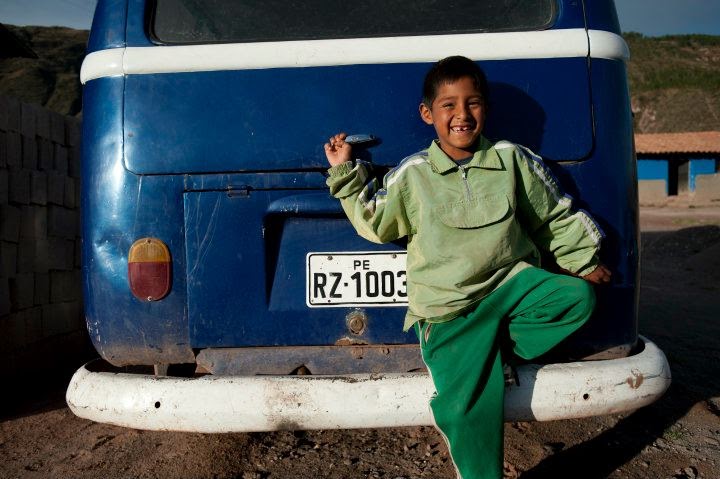

Of course, LAFF’s impact can’t fully be appreciated without considering the experiences of the beneficiaries it supports. LAFF has now reached an age that allows beneficiaries to have received support throughout their entire educational experience. For example, there are young adults who first stayed at a Sacred Valley Project dorm for the duration of their secondary schooling, before continuing to the Mosqoy house to facilitate further education at an institution in Cusco. The ability to see long-term impact serves as a reminder of LAFF’s purpose and demonstrates why LAFF focuses on improving access to and quality of education.

In celebrating LAFF’s 15th Anniversary, we have seen a fantastic amount of support both from Cusqueñan individuals and businesses, and our UK-based supporters. To raise awareness and funds in Cusco, we organised a raffle, which was lots of work but great fun. The entire team enjoyed selling the tickets, and even more so announcing the prizes, which was very exciting! We were so pleased and surprised to discover that so many businesses were eager to get involved, and in the end, we received 19 amazing prizes for restaurants, clothes and more. Additionally, for our supporters who live in the UK and couldn’t participate in the raffle, we set up a fundraising page to coordinate with our social media fundraising campaign. This was also a success, and as of writing we have reached our goal of £300! We have been very grateful for all the support and look forward to putting the funds to good use.

The final element of our celebrations is a documentary reflecting on 15 years of LAFF. It features old and new interviews from LAFF volunteers, trustees and beneficiaries, including a new interview with our founder, Sarah Oakes, who luckily happened to be in Cusco at the time of filming. This documentary, put together by Anna, our Events and Campaigns Coordinator during May to August, is a real opportunity to enjoy memories of the past, look to the future, and celebrate what LAFF has achieved thanks to the dedication and hard work of so many people. It’s definitely worth a watch, and I found it to be very touching.

I’m grateful to have joined LAFF at this time, to be able to share such an important moment in its journey, and it’s so exciting to look to the future and envision LAFF’s impact in five, ten or even another fifteen years! As for my personal wishes for LAFF, I hope that the organisation retains the uniqueness of its mission and vision, welcomes many more dedicated and passionate volunteers and continues to receive the amazing support it deserves and always has been so lucky to receive.

15 años de LAFF – Reflexiones de una voluntaria actual

Cuando me uní a LAFF como voluntaria, no sabía que una parte clave de mi papel como Coordinadora de Comunicaciones sería celebrar el 15 aniversario de LAFF a través de las redes sociales y una campaña de recaudación de fondos. Esta experiencia ha demostrado ser una oportunidad única para conocer la organización desde sus inicios hasta ahora. Examinar las historias de los beneficiarios y beneficiarias, los testimonios de voluntarios, voluntarias y las estadísticas, he podido aprender y comprender el impacto de LAFF a lo largo de los años mientras buscaba contenido y recuerdos para la celebración del 15 aniversario, una perspectiva que de otra manera no habría obtenido.

A medida que profundizaba en el archivo, descubrí cuánto ha crecido LAFF. Su viaje no solo puede medirse en términos de impacto y escala, sino también en su compromiso con sus valores fundamentales. Establecido en 2007 por su fundadora, Sarah Oakes, LAFF inicialmente extendió su apoyo a una organización local asociada: Azul Wasi, un hogar para niños en situación de vulnerabilidad. La inspiración de Sarah llevó a la creación de una ONG dedicada a facilitar el acceso a una educación de calidad, desarrollo personal y mejores oportunidades para niños, niñas y jóvenes en la región de Cusco. En el transcurso de los años siguientes, la familia LAFF se expandió, asociándose con tres nuevas organizaciones locales: Mantay, Mosqoy y el Proyecto del Valle Sagrado.

Es difícil decir cuántos voluntarios y voluntarias han compartido parte del viaje de LAFF, pero cada uno ha dejado su huella de una manera diferente al dar su tiempo y diversas habilidades. Mientras que algunos van y vienen, hay quienes se han mantenido conectados

a LAFF. El compromiso genuino y continuo de aquellos que han sido parte de los programas de LAFF es un testimonio de la autenticidad de nuestros valores y objetivos, y es reconfortante ver cuántos están interesados en mantenerse comprometidos y conectados. Muchos voluntarios y voluntarias recordarán su tiempo en LAFF como un momento muy especial y memorable en sus vidas, y sé que pensaré en mi tiempo con el equipo de LAFF con mucho cariño, como un momento de amistad y crecimiento personal. He aprendido mucho no solo en los ámbitos de la experiencia profesional, sino también con respecto a la gente, la cultura y la historia de Cusco.

Por supuesto, el impacto de LAFF no se puede apreciar plenamente sin considerar las experiencias de los beneficiarios y beneficiarias que apoya. LAFF ha alcanzado un tiempo como organización que permite a los beneficiarios y beneficiarias haber recibido apoyo a lo largo de toda su época educativa. Por ejemplo, hay adultas jóvenes que primero se quedaron en uno de los dormitorios del Proyecto Valle Sagrado durante la duración de su educación secundaria, antes de continuar en la casa Mosqoy para continuar su educación superior en una institución en Cusco. La capacidad de ver el impacto a largo plazo sirve como un recordatorio del propósito de LAFF y demuestra por qué LAFF se enfoca en mejorar el acceso y la calidad de la educación.

Al celebrar el 15 aniversario de LAFF, hemos visto una cantidad fantástica de apoyo tanto de personas y empresas cusqueñas como de nuestros colaboradores con sede en el Reino Unido. Para crear conciencia y recaudar fondos en Cusco, organizamos una rifa, que fue mucho trabajo, pero muy divertida. Todo el equipo disfrutó vendiendo las entradas, y más aún anunciando los premios, ¡lo que fue muy emocionante! Estábamos muy contentas y sorprendidas de descubrir que tantas empresas querían participar, y recibimos 19 premios increíbles para restaurantes, ropa y más. Además, para nuestros colaboradores que viven en el Reino Unido y no pudieron participar en la rifa, creamos una página de recaudación de fondos para coordinar con nuestra campaña de recaudación de fondos en las redes sociales. ¡Esto también fue un éxito, y al momento de escribir este artículo hemos alcanzado nuestro objetivo de £ 300! Hemos estado muy agradecidas por todo el apoyo y sabemos que los fondos se utilizarán bien.

El elemento final de nuestras celebraciones es un documental que reflexiona sobre los 15 años de LAFF. Presenta entrevistas antiguas y nuevas de voluntarios y voluntarias, miembros de la junta directiva y beneficiarios y beneficiarias de LAFF, e incluye una nueva entrevista con nuestra fundadora, Sarah Oakes, quien afortunadamente estaba en Cusco en el momento del rodaje. Este documental, realizado por Anna, nuestra Coordinadora de Eventos y Campañas de mayo a agosto, es una oportunidad real para disfrutar de recuerdos del pasado, mirar hacia el futuro y celebrar lo que LAFF ha logrado gracias a la dedicación y el arduo trabajo de tantas personas. Definitivamente vale la pena verlo, y me pareció muy conmovedor.

Estoy agradecida de haberme unido a LAFF en este momento, para poder compartir un momento tan importante en su viaje, ¡y es muy emocionante mirar hacia el futuro y visualizar el impacto de LAFF en cinco, diez o incluso otros quince años! En cuanto a mis deseos personales para LAFF, espero que la organización conserve la singularidad de su misión y visión, dé la bienvenida a muchos más voluntarios y voluntarias dedicados y apasionados, y continúe recibiendo el increíble apoyo que merece y siempre ha tenido la suerte de recibir.